Article Berlin Observation

Author Ingrid Schröder, Joris Fach

In Architectural Journal

Pages 6-12

Publisher The Architectural Society of China

Editorial/Text Zhou Chang

Copyright The Architectural Society of China

Berlin Observation

Abstract

This article introduces a design studio experimenting on a non-monumental approach to a Civic space in Berlin. We focused on the observation and examination Of the intricate and disconnected adhoc urbanism and monumental space, and intended to find the programs latent within this hybridized city. The observed phenomena provided a new framework for understanding the found condition, both distilling and reframing it.

Key Words

urban observation, ad-hoc urbanism, monumental space

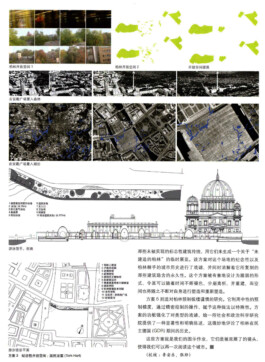

In November of last year our sixteen students spent five days in Berlin. In this limited time we could not hope to fully understand the city or provide a comprehensive documentation of its complex physical and social metabolism. We were acting as knowing tourists and design opportunists. We were seeking a possible lesson from the city‘s capacity for reinvention and informal use in order to find a new set of proposals for the troubled Schlossplatz, a space at the monumental heart of the city that has been subjected to repeated attempts to re-orientate its history. We hoped to use this highly visible and contentious site to question what sort of monumentality suits Berlin today and, more broadly, how contemporary civic representation manifests itself appropriately in a European, bankrupt capital. Our work concentrated on the relationship between space and event, and was concerned with how programs derived from our reading of the various, and occasionally nefarious, uses of the city might provide an alternative to the monumental formalism that normally characterizes the design of civic space.

When we arrived in the city we had already conducted a close investigation of the factors and priorities that had shaped the city‘s growth over the past 20 years. This drew together a set of abstract data, historic maps, secondhand anecdotes and a rich mythology derived from film and literature. But we were there to conduct a close examination of the 'programs' latent within the city. The official and unofficial transformations of Berlin were to provide us with a complex model for reconsidering the monument and monumental institution as part of public life. Alongside the construction cranes

that, after 1989, worked for two decades to guarantee a functioning capital, the city has perfected ad-hoc space-making, an expertise in temporary re-uses and low-budget urbanism that copes intelligently with the fractured, vast spaces the city has to offer. Berlin is in many ways the capital of 'pop-ups', making this now-ubiquitous phenomenon a critical part of its metabolism. Using a close analysis of these informal uses, we planned to test new alternatives for cultural constructs in the city and, more broadly, challenge the isolation of the monument, the formal manifestations of national memory, alongside the role of civic space in 21st century culture.

However our ability to read and document a city over such a brief period had significant limitations. Furthermore, we needed to question how our observations might usefully inform a design process. The first issue is relatively common to all mapping exercises and while we may understand the value of such a constraint, the results of such a remote and fleeting analysis must be set in a very particular context. When this context is the design process itself, driven by individual invention and interpretation, the objective view that such an analysis may offer is inherently suspect. Therefore, what is presented here is a knowingly unreliable witness to the phenomena we found in Berlin, further distorted by the willful eye of the architect.

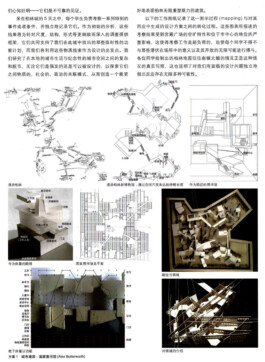

Over the five days we were in the city, each student uncovered a particular set of events or conditions and recorded these in isolation. This initial analysis came to provide the framework for a detailed investigation of the scales, structures, and forms that underpin the transient programs we found in the city, and used these physical implications as a starting point for our own designs. Our work examined the intricacies and disconnects between ad-hoc urbanism and monumental spaces, both accidental and designed, in order to exploit their physical, social and political modes of operation to t build a structure that is a better representation of Berlin‘s seemingly infinite capacity for reinvention.

The work shown in the following images charts the transition between this mapping process and the projects that emerged in response to it. The investigations that are described here are heavily influenced by the Schlossplatz site and its emptiness and centrality within the city. This provided a loaded condition that forced each student to wrestle with the potentially paralyzing significance of the site and the infinite possibility of its openness. The disparate directions of the mapping of Berlin itself became the cue for an informal reappraisal of this highly formal condition and gave way to a remarkably diverse and independent range reactions to it.

This work must be read collectively as it is the overlaying of the separate responses that provides the most valuable map of the city. This reading rests as much with the observations made by each student as with the designs that emerged. These enable the observed phenomena to be hybridized and distorted in order to provide a new framework for understanding the found condition, both distilling and reframing it.

These five projects describe an accentuation and occasionally an inversion of a found condition. In each case the proposal itself acts as a reading of the city rather than being a precise distillation of a perceived programmatic need.

The first translates the navigation of the city and the museum into a three dimensional strategy for navigating the space of the library, the pauses expressed in the early maps and models are rediscovered in the reading spaces of the scheme. Here the order of the city is replaced with the organization of knowledge.

The second project uses an analysis of hidden Berlin to reflect on the effect of memory and imagination on the nature of

experience. The kinopalast then creates an ambiguous territory in which the spaces bleed into one another and into the ruins of the Schloss. Here the unbroken and layered space necessarily distorts the cinematic experience and potentially disorientates the viewer.

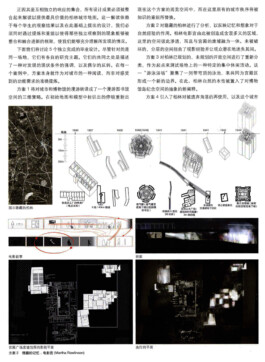

The third takes a catalogue of Berlins open spaces, planned and unplanned, as the starting point for testing a version of compressed recreation on the site. This swimming bath gathers a secession of domed pools together to form a new boundary to the Schloss site. Here Berlin‘s nature is brought into the an abstract reinterpretation of the monumental spaces of Museum Insel.

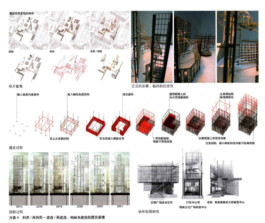

The fourth takes Berlin‘s reuse of its derelict sites and its tradition of iconic un-realized architecture as a generator for a temporary exposition of un-built Berlin. This plays on the monumentality of the site and the troubled nature of Berlin‘s history while undermining the intended permanence of the structures that it replicates. The projects are purposefully fragile and shown to fade, disintegrate and become reconstructed over time as the space makes and remakes itself.

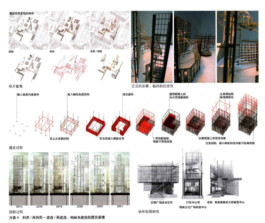

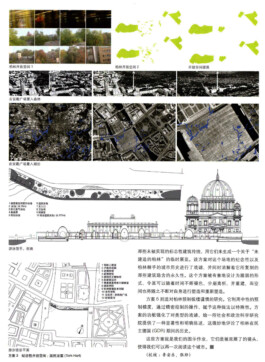

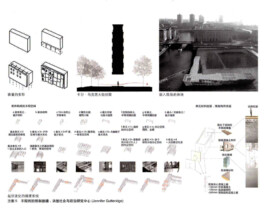

The final project is a discreet examination of the Berlin Plattenbau. It takes the neutrality of the precast module and, through a highly controlled manipulation, gives it a particularity. The program reinforced this play on type, the school of social and political science given a prominence and defined articulation that comments subtly on Berlin‘s GDR past.

These projects are our mapping, they are a developed lens with which to read the city once more.

Comment

"Taschenwelt", a little pocket world, a German concept derived from Arno Schmidt and Claude Levi-Strauss. It bespeaks a model that holds the dynamic properties of a life form, enabling a more precise view of a complex reality. It is a micro-world, in which the reduction of scale may be said to reverse a situation. This 'pocket world' can be assessed and comprehended at a glance. Can we use it in architectural and urban design? I think we can. It is an important issue in Raoul Bunschoten‘s Urban Flotsam (2001). We need to unveil other potentials in urbanism, access a rapidly changing environment. How can we ‚play‘ as designers with these newly encountered elements? We might relate this 'pocket world' to Gilles Deleuze‘s and Félix Guattari‘s reading of Kafka, a 'littératuremineure', not a small literature, but a literature of a minority speaking a great language. Condensed, but full of meaning. Like the Jews in Prague.Or Yiddish in Amsterdam. Not Classical Hebrew, but a ‚minor language‘ widespread over Europe. The limited space of the 'Taschenwelt' generates a world, as Deleuze and Guattari explain, where everything is political. The 'Taschenwelt' puts everything under the political microscope. This is how I read the Cambridge Studio of Ingrid Schröder, an exercise in reinventing a 'troubled Schlossplatz', a place so full of German History that it might suffocate the designers. It did not happen though. They invented a 'Taschenwelt', they found relations between this space and its event structure as potentiality. Navigating the space of the library, reinventing the memory of a hidden Berlin. They actually succeeded in finding this ‚alternative to the monumental formalism that normally characterizes the design of civic space‘, as she writes. They found a 'littératuremineure' in their designs, reconsidering the formal language of monumentality, the ‚official language‘ for the Schlossplatz. No classical metaphor, but as in Kafka metamorphosis is central. Whether in Berlin‘s open spaces, the reuse of its derelict sites or Berlin‘s Plattenbau reexamined.

(Commentator: Arie Graafland)

Article Berlin Observation

Author Ingrid Schröder, Joris Fach

In Architectural Journal

Pages 6-12

Publisher The Architectural Society of China

Editorial/Text Zhou Chang

Copyright The Architectural Society of China

Berlin Observation

Abstract

This article introduces a design studio experimenting on a non-monumental approach to a Civic space in Berlin. We focused on the observation and examination Of the intricate and disconnected adhoc urbanism and monumental space, and intended to find the programs latent within this hybridized city. The observed phenomena provided a new framework for understanding the found condition, both distilling and reframing it.

Key Words

urban observation, ad-hoc urbanism, monumental space

In November of last year our sixteen students spent five days in Berlin. In this limited time we could not hope to fully understand the city or provide a comprehensive documentation of its complex physical and social metabolism. We were acting as knowing tourists and design opportunists. We were seeking a possible lesson from the city‘s capacity for reinvention and informal use in order to find a new set of proposals for the troubled Schlossplatz, a space at the monumental heart of the city that has been subjected to repeated attempts to re-orientate its history. We hoped to use this highly visible and contentious site to question what sort of monumentality suits Berlin today and, more broadly, how contemporary civic representation manifests itself appropriately in a European, bankrupt capital. Our work concentrated on the relationship between space and event, and was concerned with how programs derived from our reading of the various, and occasionally nefarious, uses of the city might provide an alternative to the monumental formalism that normally characterizes the design of civic space.

When we arrived in the city we had already conducted a close investigation of the factors and priorities that had shaped the city‘s growth over the past 20 years. This drew together a set of abstract data, historic maps, secondhand anecdotes and a rich mythology derived from film and literature. But we were there to conduct a close examination of the 'programs' latent within the city. The official and unofficial transformations of Berlin were to provide us with a complex model for reconsidering the monument and monumental institution as part of public life. Alongside the construction cranes

that, after 1989, worked for two decades to guarantee a functioning capital, the city has perfected ad-hoc space-making, an expertise in temporary re-uses and low-budget urbanism that copes intelligently with the fractured, vast spaces the city has to offer. Berlin is in many ways the capital of 'pop-ups', making this now-ubiquitous phenomenon a critical part of its metabolism. Using a close analysis of these informal uses, we planned to test new alternatives for cultural constructs in the city and, more broadly, challenge the isolation of the monument, the formal manifestations of national memory, alongside the role of civic space in 21st century culture.

However our ability to read and document a city over such a brief period had significant limitations. Furthermore, we needed to question how our observations might usefully inform a design process. The first issue is relatively common to all mapping exercises and while we may understand the value of such a constraint, the results of such a remote and fleeting analysis must be set in a very particular context. When this context is the design process itself, driven by individual invention and interpretation, the objective view that such an analysis may offer is inherently suspect. Therefore, what is presented here is a knowingly unreliable witness to the phenomena we found in Berlin, further distorted by the willful eye of the architect.

Over the five days we were in the city, each student uncovered a particular set of events or conditions and recorded these in isolation. This initial analysis came to provide the framework for a detailed investigation of the scales, structures, and forms that underpin the transient programs we found in the city, and used these physical implications as a starting point for our own designs. Our work examined the intricacies and disconnects between ad-hoc urbanism and monumental spaces, both accidental and designed, in order to exploit their physical, social and political modes of operation to t build a structure that is a better representation of Berlin‘s seemingly infinite capacity for reinvention.

The work shown in the following images charts the transition between this mapping process and the projects that emerged in response to it. The investigations that are described here are heavily influenced by the Schlossplatz site and its emptiness and centrality within the city. This provided a loaded condition that forced each student to wrestle with the potentially paralyzing significance of the site and the infinite possibility of its openness. The disparate directions of the mapping of Berlin itself became the cue for an informal reappraisal of this highly formal condition and gave way to a remarkably diverse and independent range reactions to it.

This work must be read collectively as it is the overlaying of the separate responses that provides the most valuable map of the city. This reading rests as much with the observations made by each student as with the designs that emerged. These enable the observed phenomena to be hybridized and distorted in order to provide a new framework for understanding the found condition, both distilling and reframing it.

These five projects describe an accentuation and occasionally an inversion of a found condition. In each case the proposal itself acts as a reading of the city rather than being a precise distillation of a perceived programmatic need.

The first translates the navigation of the city and the museum into a three dimensional strategy for navigating the space of the library, the pauses expressed in the early maps and models are rediscovered in the reading spaces of the scheme. Here the order of the city is replaced with the organization of knowledge.

The second project uses an analysis of hidden Berlin to reflect on the effect of memory and imagination on the nature of

experience. The kinopalast then creates an ambiguous territory in which the spaces bleed into one another and into the ruins of the Schloss. Here the unbroken and layered space necessarily distorts the cinematic experience and potentially disorientates the viewer.

The third takes a catalogue of Berlins open spaces, planned and unplanned, as the starting point for testing a version of compressed recreation on the site. This swimming bath gathers a secession of domed pools together to form a new boundary to the Schloss site. Here Berlin‘s nature is brought into the an abstract reinterpretation of the monumental spaces of Museum Insel.

The fourth takes Berlin‘s reuse of its derelict sites and its tradition of iconic un-realized architecture as a generator for a temporary exposition of un-built Berlin. This plays on the monumentality of the site and the troubled nature of Berlin‘s history while undermining the intended permanence of the structures that it replicates. The projects are purposefully fragile and shown to fade, disintegrate and become reconstructed over time as the space makes and remakes itself.

The final project is a discreet examination of the Berlin Plattenbau. It takes the neutrality of the precast module and, through a highly controlled manipulation, gives it a particularity. The program reinforced this play on type, the school of social and political science given a prominence and defined articulation that comments subtly on Berlin‘s GDR past.

These projects are our mapping, they are a developed lens with which to read the city once more.

Comment

"Taschenwelt", a little pocket world, a German concept derived from Arno Schmidt and Claude Levi-Strauss. It bespeaks a model that holds the dynamic properties of a life form, enabling a more precise view of a complex reality. It is a micro-world, in which the reduction of scale may be said to reverse a situation. This 'pocket world' can be assessed and comprehended at a glance. Can we use it in architectural and urban design? I think we can. It is an important issue in Raoul Bunschoten‘s Urban Flotsam (2001). We need to unveil other potentials in urbanism, access a rapidly changing environment. How can we ‚play‘ as designers with these newly encountered elements? We might relate this 'pocket world' to Gilles Deleuze‘s and Félix Guattari‘s reading of Kafka, a 'littératuremineure', not a small literature, but a literature of a minority speaking a great language. Condensed, but full of meaning. Like the Jews in Prague.Or Yiddish in Amsterdam. Not Classical Hebrew, but a ‚minor language‘ widespread over Europe. The limited space of the 'Taschenwelt' generates a world, as Deleuze and Guattari explain, where everything is political. The 'Taschenwelt' puts everything under the political microscope. This is how I read the Cambridge Studio of Ingrid Schröder, an exercise in reinventing a 'troubled Schlossplatz', a place so full of German History that it might suffocate the designers. It did not happen though. They invented a 'Taschenwelt', they found relations between this space and its event structure as potentiality. Navigating the space of the library, reinventing the memory of a hidden Berlin. They actually succeeded in finding this ‚alternative to the monumental formalism that normally characterizes the design of civic space‘, as she writes. They found a 'littératuremineure' in their designs, reconsidering the formal language of monumentality, the ‚official language‘ for the Schlossplatz. No classical metaphor, but as in Kafka metamorphosis is central. Whether in Berlin‘s open spaces, the reuse of its derelict sites or Berlin‘s Plattenbau reexamined.

(Commentator: Arie Graafland)